On 25th May 2020, an African-American citizen of Minneapolis was killed by police during his arrest for allegedly using counterfeit money to buy cigarettes. He died after a white police officer knelt on his neck and back for over eight minutes. His death has sparked various international Black Lives Matter protests, with calls for action to address police reform as well as racial inequalities throughout society.

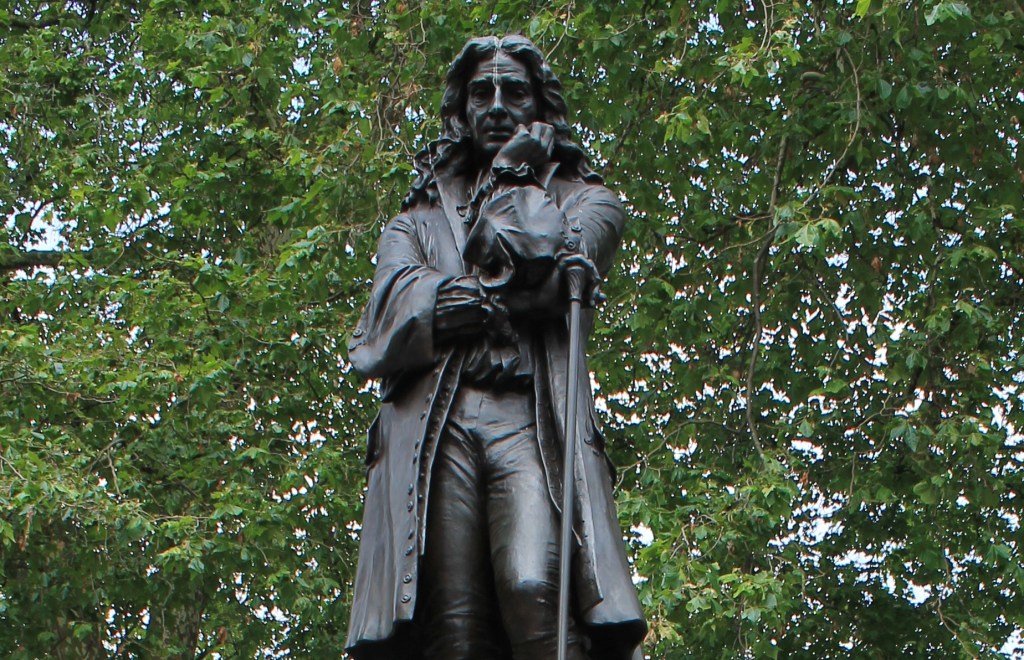

Across the Atlantic, protests in British cities sparked a series of actions against racially or culturally insensitive commemorative statues and memorials. In the city of Bristol, on Sunday 7th June 2020, a crowd of protesters pulled down the statue of 17th century slave-trader, Edward Colston. The statue had stood on a large plinth in the city centre for 125 years since it was erected in 1895, over 170 years after his death. It was erected as a memorial to an allegedly ‘wise and virtuous’ man whose contributions to philanthropic causes in the city were considered worth remembering. Colston was a member of the governing body of the Royal African Company and he made his money through trading in enslaved African people – a fact of great significance which was conspicuous by its absence from the memorial text on the statue. Colston may have contributed large sums of money to charitable causes for the people of Bristol, but he did so with money stained with the blood of thousands of enslaved people from Africa, many of whom died in their shackles before they even made it to Britain and the Americas. It is notable that this information about Colston was not considered worth remembering, either at the time of the statue’s construction or even in the 21st century when a campaign to have it added to the plaques on the statue failed in its ambition. Bristol has always struggled to come to terms with its history and its own part in the 400 years of slavery of African people.

The continued acceptance of the culturally biased memorial statue of Colston and the in-ability to accept attempts to provide more balanced information on his legacy is symptomatic not only of the morally charged struggle with Bristol’s history, but also of the wider racial and cultural bias in our society today. The Impact of Omission survey, released on the 1st June 2020, found that less than 10% of school children in the UK learned about the role of slavery in British industrialisation or Britain’s colonisation of Africa. For better or for worse, Britain and its empire had a huge impact on many countries, peoples and cultures. If we simply remove the unsavoury parts of our history from view, rather than get better at teaching people about them, we risk allowing racism and prejudice to fester where there is ignorance. Until we face up to and come to terms with our role in historical events such as slavery, and take real action to rectify both the misdeeds of the past and the continued racial and cultural bias and insensitivity of today, we will forever live in fear of history’s shadow and allow our society to remain culturally biased and repressed.

So, where do statues stand in all of this? Many statues are erected not as a form of historical education, but rather as forms of political or cultural imposition. They are political statements of biased agendas. A statue teaches us to revere and admire a person, rather than their actions, words, or role in historical events. By focusing on the physical likeness of the person themselves, rather than on the reason why they have been chosen to be commemorated, we allow ourselves to forget a fundamental truth. What makes historical figures worth remembering is not their physical likeness, but their words and actions. Without the context of their role in historical events, both positive and negative, a statue or memorial is intrinsically biased and worthless as an historical aid. Instead, it is just the physical demonstration of power or political agendas that hide or even deny the reality of the individual’s place in history. As such, statues have no place in an enlightened, democratic and multicultural society.

When Colston’s statue was torn down from its plinth and laid on the ground, the veil over the reality of Colston’s role in history was finally lifted. Removed from his pedestal and lying on the ground at the feet of the protesters, the figure of Colston lost its power as a form of political oppression. He was dragged through the streets and dropped over the side of the harbour to lie in a watery grave, much like the African souls who died and were dropped over the side of the slave ships to a grave at the bottom of the ocean. Colston’s statue now lies at the bottom of the harbour in which his ships once transported thousands of enslaved human beings in cast iron shackles. The symmetry of this act is very poetic and represents a powerful and poignant moment in Bristol’s contemporary history.

The vacant public space left by Colston’s statue represents an opportunity to create a powerful shift in methods of public memorial and commemoration. Some are suggesting a new statue of former slaves or culturally significant figures representing the diversity of our modern society. While this is a potentially powerful statement, perhaps an alternative suggestion would be a non-individual centric memorial to Bristol’s slavery history or modern cultural identity. Perhaps an object or word centred piece of public art would be an alternative and just as powerful form of public remembrance. Whatever is eventually chosen, we must now ask ourselves if we are brave enough to take this opportunity, not only to recognise slavery as a part of Bristol’s history and the lives it affected and destroyed, but also to finally dispense with methods of political or cultural oppression that are personified in statues, which focus our attention and reverence on the physical likeness of an individual, rather than the actions or words, positive or negative, that make them significant and important to remember.

Article written by Stephen J. Dunning. Photograph of Colston statue by Simon Cobb, taken on 24 June 2019, and published via Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a comment